As a final example of inheritance, we’ll extend our text-query application from §12.3 (p. 484). The classes we wrote in that section let us look for occurrences of a given word in a file. We’d like to extend the system to support more complicated queries. In our examples, we’ll run queries against the following simple story:

Alice Emma has long flowing red hair.

Her Daddy says when the wind blows

through her hair, it looks almost alive,

like a fiery bird in flight.

A beautiful fiery bird, he tells her,

magical but untamed.

"Daddy, shush, there is no such thing,"

she tells him, at the same time wanting

him to tell her more.

Shyly, she asks, "I mean, Daddy, is there?"

Our system should support the following queries:

• Word queries find all the lines that match a given

string:

Executing Query for:

Daddy Daddy occurs 3 times

(line 2) Her Daddy says when the wind blows

(line 7) "Daddy, shush, there is no such thing,"

(line 10) Shyly, she asks, "I mean, Daddy, is there?"

• Not queries, using the

~operator, yield lines that don’t match the query:

Executing Query for: ~(Alice)

~(Alice) occurs 9 times

(line 2) Her Daddy says when the wind blows

(line 3) through her hair, it looks almost alive,

(line 4) like a fiery bird in flight.

...

• Or queries, using the

|operator, return lines matching either of two queries:

Executing Query for: (hair | Alice)

(hair | Alice) occurs 2 times

(line 1) Alice Emma has long flowing red hair.

(line 3) through her hair, it looks almost alive,

• And queries, using the

&operator, return lines matching both queries:

Executing query for: (hair & Alice)

(hair & Alice) occurs 1 time

(line 1) Alice Emma has long flowing red hair.

Moreover, we want to be able to combine these operations, as in

fiery & bird | wind

We’ll use normal C++ precedence rules (§4.1.2, p. 136) to evaluate compound expressions such as this example. Thus, this query will match a line in which both fiery and bird appear or one in which wind appears:

Executing Query for: ((fiery & bird) | wind)

((fiery & bird) | wind) occurs 3 times

(line 2) Her Daddy says when the wind blows

(line 4) like a fiery bird in flight.

(line 5) A beautiful fiery bird, he tells her,

Our output will print the query, using parentheses to indicate the way in which the query was interpreted. As with our original implementation, our system will display lines in ascending order and will not display the same line more than once.

We might think that we should use the TextQuery class from §12.3.2 (p. 487) to represent our word query and derive our other queries from that class.

However, this design would be flawed. To see why, consider a Not query. A Word query looks for a particular word. In order for a Not query to be a kind of Word query, we would have to be able to identify the word for which the Not query was searching. In general, there is no such word. Instead, a Not query has a query (a Word query or any other kind of query) whose value it negates. Similarly, an And query and an Or query have two queries whose results it combines.

This observation suggests that we model our different kinds of queries as independent classes that share a common base class:

WordQuery // Daddy

NotQuery // ~Alice

OrQuery // hair | Alice

AndQuery // hair & Alice

These classes will have only two operations:

•

eval, which takes aTextQueryobject and returns aQueryResult. Theevalfunction will use the givenTextQueryobject to find the query’s the matching lines.

•

rep, which returns thestringrepresentation of the underlying query. This function will be used byevalto create aQueryResultrepresenting the match and by the output operator to print the query expressions.

As we’ve seen, our four query types are not related to one another by inheritance; they are conceptually siblings. Each class shares the same interface, which suggests that we’ll need to define an abstract base class (§15.4, p. 610) to represent that interface. We’ll name our abstract base class Query_base, indicating that its role is to serve as the root of our query hierarchy.

Our Query_base class will define eval and rep as pure virtual functions (§15.4, p. 610). Each of our classes that represents a particular kind of query must override these functions. We’ll derive WordQuery and NotQuery directly from Query_base. The AndQuery and OrQuery classes share one property that the other classes in our system do not: Each has two operands. To model this property, we’ll define another abstract base class, named BinaryQuery, to represent queries with two operands. The AndQuery and OrQuery classes will inherit from BinaryQuery, which in turn will inherit from Query_base. These decisions give us the class design represented in Figure 15.2.

Figure 15.2. Query_base Inheritance Hierarchy

The design of inheritance hierarchies is a complicated topic in its own right and well beyond the scope of this language Primer. However, there is one important design guide that is so fundamental that every programmer should be familiar with it.

When we define a class as publicly inherited from another, the derived class should reflect an “Is A” relationship to the base class. In well-designed class hierarchies, objects of a publicly derived class can be used wherever an object of the base class is expected.

Another common relationship among types is a “Has A” relationship. Types related by a “Has A” relationship imply membership.

In our bookstore example, our base class represents the concept of a quote for a book sold at a stipulated price. Our

Bulk_quote“is a” kind of quote, but one with a different pricing strategy. Our bookstore classes “have a” price and an ISBN.

Our program will deal with evaluating queries, not with building them. However, we need to be able to create queries in order to run our program. The simplest way to do so is to write C++ expressions to create the queries. For example, we’d like to generate the compound query previously described by writing code such as

Query q = Query("fiery") & Query("bird") | Query("wind");

This problem description implicitly suggests that user-level code won’t use the inherited classes directly. Instead, we’ll define an interface class named Query, which will hide the hierarchy. The Query class will store a pointer to Query_base. That pointer will be bound to an object of a type derived from Query_base. The Query class will provide the same operations as the Query_base classes: eval to evaluate the associated query, and rep to generate a string version of the query. It will also define an overloaded output operator to display the associated query.

Users will create and manipulate Query_base objects only indirectly through operations on Query objects. We’ll define three overloaded operators on Query objects, along with a Query constructor that takes a string. Each of these functions will dynamically allocate a new object of a type derived from Query_base:

• The

&operator will generate aQuerybound to a newAndQuery.

• The

|operator will generate aQuerybound to a newOrQuery.

• The

~operator will generate aQuerybound to a newNotQuery.

• The

Queryconstructor that takes astringwill generate a newWordQuery.

It is important to realize that much of the work in this application consists of building objects to represent the user’s query. For example, an expression such as the one above generates the collection of interrelated objects illustrated in Figure 15.3.

Figure 15.3. Objects Created by Query Expressions

Once the tree of objects is built up, evaluating (or generating the representation of) a query is basically a process (managed for us by the compiler) of following these links, asking each object to evaluate (or display) itself. For example, if we call eval on q (i.e., on the root of the tree), that call asks the OrQuery to which q points to eval itself. Evaluating this OrQuery calls eval on its two operands—on the AndQuery and the WordQuery that looks for the word wind. Evaluating the AndQuery evaluates its two WordQuerys, generating the results for the words fiery and bird, respectively.

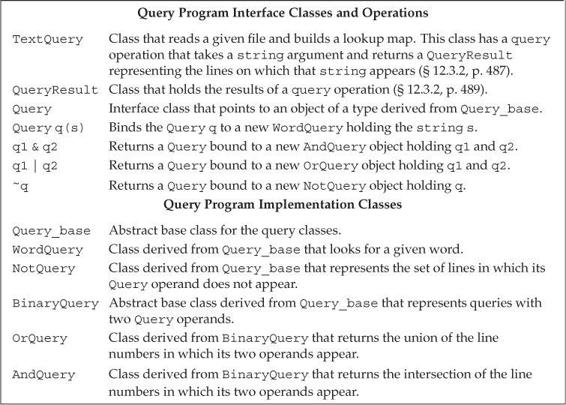

When new to object-oriented programming, it is often the case that the hardest part in understanding a program is understanding the design. Once you are thoroughly comfortable with the design, the implementation flows naturally. As an aid to understanding this design, we’ve summarized the classes used in this example in Table 15.1 (overleaf).

Table 15.1. Recap: Query Program Design

Exercises Section 15.9.1

Exercise 15.31: Given that

s1,s2,s3, ands4are allstrings, determine what objects are created in the following expressions:(a)

Query(s1) | Query(s2) & ~ Query(s3);(b)

Query(s1) | (Query(s2) & ~ Query(s3));(c)

(Query(s1) & (Query(s2)) | (Query(s3) & Query(s4)));

Query_base and Query ClassesWe’ll start our implementation by defining the Query_base class:

// abstract class acts as a base class for concrete query types; all members are private

class Query_base {

friend class Query;

protected:

using line_no = TextQuery::line_no; // used in the eval functions

virtual ~Query_base() = default;

private:

// eval returns the QueryResult that matches this Query

virtual QueryResult eval(const TextQuery&) const = 0;

// rep is a string representation of the query

virtual std::string rep() const = 0;

};

Both eval and rep are pure virtual functions, which makes Query_base an abstract base class (§15.4, p. 610). Because we don’t intend users, or the derived classes, to use Query_base directly, Query_base has no public members. All use of Query_base will be through Query objects. We grant friendship to the Query class, because members of Query will call the virtuals in Query_base.

The protected member, line_no, will be used inside the eval functions. Similarly, the destructor is protected because it is used (implicitly) by the destructors in the derived classes.

Query ClassThe Query class provides the interface to (and hides) the Query_base inheritance hierarchy. Each Query object will hold a shared_ptr to a corresponding Query_base object. Because Query is the only interface to the Query_base classes, Query must define its own versions of eval and rep.

The Query constructor that takes a string will create a new WordQuery and bind its shared_ptr member to that newly created object. The &, |, and ~ operators will create AndQuery, OrQuery, and NotQuery objects, respectively. These operators will return a Query object bound to its newly generated object. To support these operators, Query needs a constructor that takes a shared_ptr to a Query_base and stores its given pointer. We’ll make this constructor private because we don’t intend general user code to define Query_base objects. Because this constructor is private, we’ll need to make the operators friends.

Given the preceding design, the Query class itself is simple:

// interface class to manage the Query_base inheritance hierarchy

class Query {

// these operators need access to the shared_ptr constructor

friend Query operator~(const Query &);

friend Query operator|(const Query&, const Query&);

friend Query operator&(const Query&, const Query&);

public:

Query(const std::string&); // builds a new WordQuery

// interface functions: call the corresponding Query_base operations

QueryResult eval(const TextQuery &t) const

{ return q->eval(t); }

std::string rep() const { return q->rep(); }

private:

Query(std::shared_ptr<Query_base> query): q(query) { }

std::shared_ptr<Query_base> q;

};

We start by naming as friends the operators that create Query objects. These operators need to be friends in order to use the private constructor.

In the public interface for Query, we declare, but cannot yet define, the constructor that takes a string. That constructor creates a WordQuery object, so we cannot define this constructor until we have defined the WordQuery class.

The other two public members represent the interface for Query_base. In each case, the Query operation uses its Query_base pointer to call the respective (virtual) Query_base operation. The actual version that is called is determined at run time and will depend on the type of the object to which q points.

Query Output Operator

The output operator is a good example of how our overall query system works:

std::ostream &

operator<<(std::ostream &os, const Query &query)

{

// Query::rep makes a virtual call through its Query_base pointer to rep()

return os << query.rep();

}

When we print a Query, the output operator calls the (public) rep member of class Query. That function makes a virtual call through its pointer member to the rep member of the object to which this Query points. That is, when we write

Query andq = Query(sought1) & Query(sought2);

cout << andq << endl;

the output operator calls Query::rep on andq. Query::rep in turn makes a virtual call through its Query_base pointer to the Query_base version of rep. Because andq points to an AndQuery object, that call will run AndQuery::rep.

Exercises Section 15.9.2

Exercise 15.32: What happens when an object of type

Queryis copied, moved, assigned, and destroyed?

The most interesting part of the classes derived from Query_base is how they are represented. The WordQuery class is most straightforward. Its job is to hold the search word.

The other classes operate on one or two operands. A NotQuery has a single operand, and AndQuery and OrQuery have two operands. In each of these classes, the operand(s) can be an object of any of the concrete classes derived from Query_base: A NotQuery can be applied to a WordQuery, an AndQuery, an OrQuery, or another NotQuery. To allow this flexibility, the operands must be stored as pointers to Query_base. That way we can bind the pointer to whichever concrete class we need.

However, rather than storing a Query_base pointer, our classes will themselves use a Query object. Just as user code is simplified by using the interface class, we can simplify our own class code by using the same class.

Now that we know the design for these classes, we can implement them.

WordQuery ClassA WordQuery looks for a given string. It is the only operation that actually performs a query on the given TextQuery object:

class WordQuery: public Query_base {

friend class Query; // Query uses the WordQuery constructor

WordQuery(const std::string &s): query_word(s) { }

// concrete class: WordQuery defines all inherited pure virtual functions

QueryResult eval(const TextQuery &t) const

{ return t.query(query_word); }

std::string rep() const { return query_word; }

std::string query_word; // word for which to search

};

Like Query_base, WordQuery has no public members; WordQuery must make Query a friend in order to allow Query to access the WordQuery constructor.

Each of the concrete query classes must define the inherited pure virtual functions, eval and rep. We defined both operations inside the WordQuery class body: eval calls the query member of its given TextQuery parameter, which does the actual search in the file; rep returns the string that this WordQuery represents (i.e., query_word).

Having defined the WordQuery class, we can now define the Query constructor that takes a string:

inline

Query::Query(const std::string &s): q(new WordQuery(s)) { }

This constructor allocates a WordQuery and initializes its pointer member to point to that newly allocated object.

NotQuery Class and the ~ OperatorThe ~ operator generates a NotQuery, which holds a Query, which it negates:

class NotQuery: public Query_base {

friend Query operator~(const Query &);

NotQuery(const Query &q): query(q) { }

// concrete class: NotQuery defines all inherited pure virtual functions

std::string rep() const {return "~(" + query.rep() + ")";}

QueryResult eval(const TextQuery&) const;

Query query;

};

inline Query operator~(const Query &operand)

{

return std::shared_ptr<Query_base>(new NotQuery(operand));

}

Because the members of NotQuery are all private, we start by making the ~ operator a friend. To rep a NotQuery, we concatenate the ~ symbol to the representation of the underlying Query. We parenthesize the output to ensure that precedence is clear to the reader.

It is worth noting that the call to rep in NotQuery’s own rep member ultimately makes a virtual call to rep: query.rep() is a nonvirtual call to the rep member of the Query class. Query::rep in turn calls q->rep(), which is a virtual call through its Query_base pointer.

The ~ operator dynamically allocates a new NotQuery object. The return (implicitly) uses the Query constructor that takes a shared_ptr<Query_base>. That is, the return statement is equivalent to

// allocate a new NotQuery object

// bind the resulting NotQuery pointer to a shared_ptr<Query_base

shared_ptr<Query_base> tmp(new NotQuery(expr));

return Query(tmp); // use the Query constructor that takes a shared_ptr

The eval member is complicated enough that we will implement it outside the class body. We’ll define the eval functions in §15.9.4 (p. 647).

BinaryQuery ClassThe BinaryQuery class is an abstract base class that holds the data needed by the query types that operate on two operands:

class BinaryQuery: public Query_base {

protected:

BinaryQuery(const Query &l, const Query &r, std::string s):

lhs(l), rhs(r), opSym(s) { }

// abstract class: BinaryQuery doesn't define eval

std::string rep() const { return "(" + lhs.rep() + " "

+ opSym + " "

+ rhs.rep() + ")"; }

Query lhs, rhs; // right- and left-hand operands

std::string opSym; // name of the operator

};

The data in a BinaryQuery are the two Query operands and the corresponding operator symbol. The constructor takes the two operands and the operator symbol, each of which it stores in the corresponding data members.

To rep a BinaryOperator, we generate the parenthesized expression consisting of the representation of the left-hand operand, followed by the operator, followed by the representation of the right-hand operand. As when we displayed a NotQuery, the calls to rep ultimately make virtual calls to the rep function of the Query_base objects to which lhs and rhs point.

The

BinaryQueryclass does not define theevalfunction and so inherits a pure virtual. Thus,BinaryQueryis also an abstract base class, and we cannot create objects ofBinaryQuerytype.

AndQuery and OrQuery Classes and Associated OperatorsThe AndQuery and OrQuery classes, and their corresponding operators, are quite similar to one another:

class AndQuery: public BinaryQuery {

friend Query operator& (const Query&, const Query&);

AndQuery(const Query &left, const Query &right):

BinaryQuery(left, right, "&") { }

// concrete class: AndQuery inherits rep and defines the remaining pure virtual

QueryResult eval(const TextQuery&) const;

};

inline Query operator&(const Query &lhs, const Query &rhs)

{

return std::shared_ptr<Query_base>(new AndQuery(lhs, rhs));

}

class OrQuery: public BinaryQuery {

friend Query operator|(const Query&, const Query&);

OrQuery(const Query &left, const Query &right):

BinaryQuery(left, right, "|") { }

QueryResult eval(const TextQuery&) const;

};

inline Query operator|(const Query &lhs, const Query &rhs)

{

return std::shared_ptr<Query_base>(new OrQuery(lhs, rhs));

}

These classes make the respective operator a friend and define a constructor to create their BinaryQuery base part with the appropriate operator. They inherit the BinaryQuery definition of rep, but each overrides the eval function.

Like the ~ operator, the & and | operators return a shared_ptr bound to a newly allocated object of the corresponding type. That shared_ptr gets converted to Query as part of the return statement in each of these operators.

Exercises Section 15.9.3

Exercise 15.34: For the expression built in Figure 15.3 (p. 638):

(a) List the constructors executed in processing that expression.

(b) List the calls to

repthat are made fromcout << q.(c) List the calls to

evalmade fromq.eval().Exercise 15.35: Implement the

QueryandQuery_baseclasses, including a definition ofrepbut omitting the definition ofeval.Exercise 15.36: Put print statements in the constructors and

repmembers and run your code to check your answers to(a)and(b)from the first exercise.Exercise 15.37: What changes would your classes need if the derived classes had members of type

shared_ptr<Query_base>rather than of typeQuery?Exercise 15.38: Are the following declarations legal? If not, why not? If so, explain what the declarations mean.

BinaryQuery a = Query("fiery") & Query("bird");

AndQuery b = Query("fiery") & Query("bird");

OrQuery c = Query("fiery") & Query("bird");

eval FunctionsThe eval functions are the heart of our query system. Each of these functions calls eval on its operand(s) and then applies its own logic: The OrQuery eval operation returns the union of the results of its two operands; AndQuery returns the intersection. The NotQuery is more complicated: It must return the line numbers that are not in its operand’s set.

To support the processing in the eval functions, we need to use the version of QueryResult that defines the members we added in the exercises to §12.3.2 (p. 490). We’ll assume that QueryResult has begin and end members that will let us iterate through the set of line numbers that the QueryResult holds. We’ll also assume that QueryResult has a member named get_file that returns a shared_ptr to the underlying file on which the query was executed.

OrQuery::evalAn OrQuery represents the union of the results for its two operands, which we obtain by calling eval on each of its operands. Because these operands are Query objects, calling eval is a call to Query::eval, which in turn makes a virtual call to eval on the underlying Query_base object. Each of these calls yields a QueryResult representing the line numbers in which its operand appears. We’ll combine those line numbers into a new set:

// returns the union of its operands' result sets

QueryResult

OrQuery::eval(const TextQuery& text) const

{

// virtual calls through the Query members, lhs and rhs

// the calls to eval return the QueryResult for each operand

auto right = rhs.eval(text), left = lhs.eval(text);

// copy the line numbers from the left-hand operand into the result set

auto ret_lines =

make_shared<set<line_no>>(left.begin(), left.end());

// insert lines from the right-hand operand

ret_lines->insert(right.begin(), right.end());

// return the new QueryResult representing the union of lhs and rhs

return QueryResult(rep(), ret_lines, left.get_file());

}

We initialize ret_lines using the set constructor that takes a pair of iterators. The begin and end members of a QueryResult return iterators into that object’s set of line numbers. So, ret_lines is created by copying the elements from left’s set. We next call insert on ret_lines to insert the elements from right. After this call, ret_lines contains the line numbers that appear in either left or right.

The eval function ends by building and returning a QueryResult representing the combined match. The QueryResult constructor (§12.3.2, p. 489) takes three arguments: a string representing the query, a shared_ptr to the set of matching line numbers, and a shared_ptr to the vector that represents the input file. We call rep to generate the string and get_file to obtain the shared_ptr to the file. Because both left and right refer to the same file, it doesn’t matter which of these we use for get_file.

AndQuery::evalThe AndQuery version of eval is similar to the OrQuery version, except that it calls a library algorithm to find the lines in common to both queries:

// returns the intersection of its operands' result sets

QueryResult

AndQuery::eval(const TextQuery& text) const

{

// virtual calls through the Query operands to get result sets for the operands

auto left = lhs.eval(text), right = rhs.eval(text);

// set to hold the intersection of left and right

auto ret_lines = make_shared<set<line_no>>();

// writes the intersection of two ranges to a destination iterator

// destination iterator in this call adds elements to ret

set_intersection(left.begin(), left.end(),

right.begin(), right.end(),

inserter(*ret_lines, ret_lines->begin()));

return QueryResult(rep(), ret_lines, left.get_file());

}

Here we use the library set_intersection algorithm, which is described in Appendix A.2.8 (p. 880), to merge these two sets.

The set_intersection algorithm takes five iterators. It uses the first four to denote two input sequences (§10.5.2, p. 413). Its last argument denotes a destination. The algorithm writes the elements that appear in both input sequences into the destination.

In this call we pass an insert iterator (§10.4.1, p. 401) as the destination. When set_intersection writes to this iterator, the effect will be to insert a new element into ret_lines.

Like the OrQuery eval function, this one ends by building and returning a QueryResult representing the combined match.

NotQuery::evalNotQuery finds each line of the text within which the operand is not found:

// returns the lines not in its operand's result set

QueryResult

NotQuery::eval(const TextQuery& text) const

{

// virtual call to eval through the Query operand

auto result = query.eval(text);

// start out with an empty result set

auto ret_lines = make_shared<set<line_no>>();

// we have to iterate through the lines on which our operand appears

auto beg = result.begin(), end = result.end();

// for each line in the input file, if that line is not in result,

// add that line number to ret_lines

auto sz = result.get_file()->size();

for (size_t n = 0; n != sz; ++n) {

// if we haven't processed all the lines in result

// check whether this line is present

if (beg == end || *beg != n)

ret_lines->insert(n); // if not in result, add this line

else if (beg != end)

++beg; // otherwise get the next line number in result if there is one

}

return QueryResult(rep(), ret_lines, result.get_file());

}

As in the other eval functions, we start by calling eval on this object’s operand. That call returns the QueryResult containing the line numbers on which the operand appears, but we want the line numbers on which the operand does not appear. That is, we want every line in the file that is not already in result.

We generate that set by iterating through sequenital integers up to the size of the input file. We’ll put each number that is not in result into ret_lines. We position beg and end to denote the first and one past the last elements in result. That object is a set, so when we iterate through it, we’ll obtain the line numbers in ascending order.

The loop body checks whether the current number is in result. If not, we add that number to ret_lines. If the number is in result, we increment beg, which is our iterator into result.

Once we’ve processed all the line numbers, we return a QueryResult containing ret_lines, along with the results of running rep and get_file as in the previous eval functions.

Exercises Section 15.9.4

Exercise 15.39: Implement the

QueryandQuery_baseclasses. Test your application by evaluating and printing a query such as the one in Figure 15.3 (p. 638).Exercise 15.40: In the

OrQuery evalfunction what would happen if itsrhsmember returned an empty set? What if itslhsmember did so? What if bothrhsandlhsreturned empty sets?Exercise 15.41: Reimplement your classes to use built-in pointers to

Query_baserather thanshared_ptrs. Remember that your classes will no longer be able to use the synthesized copy-control members.Exercise 15.42: Design and implement one of the following enhancements:

(a) Print words only once per sentence rather than once per line.

(b) Introduce a history system in which the user can refer to a previous query by number, possibly adding to it or combining it with another.

(c) Allow the user to limit the results so that only matches in a given range of lines are displayed.