C++ defines a set of primitive types that include the arithmetic types and a special type named void. The arithmetic types represent characters, integers, boolean values, and floating-point numbers. The void type has no associated values and can be used in only a few circumstances, most commonly as the return type for functions that do not return a value.

The arithmetic types are divided into two categories: integral types (which include character and boolean types) and floating-point types.

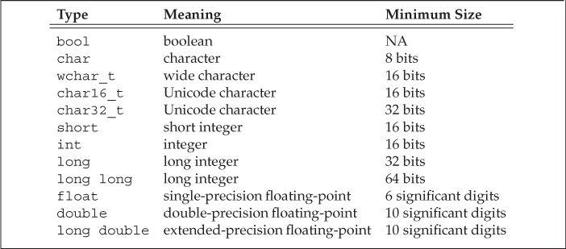

The size of—that is, the number of bits in—the arithmetic types varies across machines. The standard guarantees minimum sizes as listed in Table 2.1. However, compilers are allowed to use larger sizes for these types. Because the number of bits varies, the largest (or smallest) value that a type can represent also varies.

Table 2.1. C++: Arithmetic Types

The bool type represents the truth values true and false.

There are several character types, most of which exist to support internationalization. The basic character type is char. A char is guaranteed to be big enough to hold numeric values corresponding to the characters in the machine’s basic character set. That is, a char is the same size as a single machine byte.

The remaining character types—wchar_t, char16_t, and char32_t—are used for extended character sets. The wchar_t type is guaranteed to be large enough to hold any character in the machine’s largest extended character set. The types char16_t and char32_t are intended for Unicode characters. (Unicode is a standard for representing characters used in essentially any natural language.)

The remaining integral types represent integer values of (potentially) different sizes. The language guarantees that an int will be at least as large as short, a long at least as large as an int, and long long at least as large as long. The type long long was introduced by the new standard.

Computers store data as a sequence of bits, each holding a 0 or 1, such as

00011011011100010110010000111011 ...

Most computers deal with memory as chunks of bits of sizes that are powers of 2. The smallest chunk of addressable memory is referred to as a “byte.” The basic unit of storage, usually a small number of bytes, is referred to as a “word.” In C++ a byte has at least as many bits as are needed to hold a character in the machine’s basic character set. On most machines a byte contains 8 bits and a word is either 32 or 64 bits, that is, 4 or 8 bytes.

Most computers associate a number (called an “address”) with each byte in memory. On a machine with 8-bit bytes and 32-bit words, we might view a word of memory as follows

Here, the byte’s address is on the left, with the 8 bits of the byte following the address.

We can use an address to refer to any of several variously sized collections of bits starting at that address. It is possible to speak of the word at address 736424 or the byte at address 736427. To give meaning to memory at a given address, we must know the type of the value stored there. The type determines how many bits are used and how to interpret those bits.

If the object at location 736424 has type

floatand iffloats on this machine are stored in 32 bits, then we know that the object at that address spans the entire word. The value of thatfloatdepends on the details of how the machine stores floating-point numbers. Alternatively, if the object at location 736424 is anunsigned charon a machine using the ISO-Latin-1 character set, then the byte at that address represents a semicolon.

The floating-point types represent single-, double-, and extended-precision values. The standard specifies a minimum number of significant digits. Most compilers provide more precision than the specified minimum. Typically, floats are represented in one word (32 bits), doubles in two words (64 bits), and long doubles in either three or four words (96 or 128 bits). The float and double types typically yield about 7 and 16 significant digits, respectively. The type long double

is often used as a way to accommodate special-purpose floating-point hardware; its precision is more likely to vary from one implementation to another.

Except for bool and the extended character types, the integral types may be signed or unsigned. A signed type represents negative or positive numbers (including zero); an unsigned type represents only values greater than or equal to zero.

The types int, short, long, and long long are all signed. We obtain the corresponding unsigned type by adding unsigned to the type, such as unsigned long. The type unsigned int may be abbreviated as unsigned.

Unlike the other integer types, there are three distinct basic character types: char, signed char, and unsigned char. In particular, char is not the same type as signed char. Although there are three character types, there are only two representations: signed and unsigned. The (plain) char type uses one of these representations. Which of the other two character representations is equivalent to char depends on the compiler.

In an unsigned type, all the bits represent the value. For example, an 8-bit unsigned char can hold the values from 0 through 255 inclusive.

The standard does not define how signed types are represented, but does specify that the range should be evenly divided between positive and negative values. Hence, an 8-bit signed char is guaranteed to be able to hold values from –127 through 127; most modern machines use representations that allow values from –128 through 127.

C++, like C, is designed to let programs get close to the hardware when necessary. The arithmetic types are defined to cater to the peculiarities of various kinds of hardware. Accordingly, the number of arithmetic types in C++ can be bewildering. Most programmers can (and should) ignore these complexities by restricting the types they use. A few rules of thumb can be useful in deciding which type to use:

• Use an unsigned type when you know that the values cannot be negative.

• Use

intfor integer arithmetic.shortis usually too small and, in practice,longoften has the same size asint. If your data values are larger than the minimum guaranteed size of anint, then uselong long.• Do not use plain

charorboolin arithmetic expressions. Use them only to hold characters or truth values. Computations usingcharare especially problematic becausecharissignedon some machines andunsignedon others. If you need a tiny integer, explicitly specify eithersigned charorunsigned char.• Use

doublefor floating-point computations;floatusually does not have enough precision, and the cost of double-precision calculations versus single-precision is negligible. In fact, on some machines, double-precision operations are faster than single. The precision offered bylong doubleusually is unnecessary and often entails considerable run-time cost.

Exercises Section 2.1.1

Exercise 2.1: What are the differences between

int,long,long long, andshort? Between an unsigned and a signed type? Between afloatand adouble?Exercise 2.2: To calculate a mortgage payment, what types would you use for the rate, principal, and payment? Explain why you selected each type.

The type of an object defines the data that an object might contain and what operations that object can perform. Among the operations that many types support is the ability to convert objects of the given type to other, related types.

Type conversions happen automatically when we use an object of one type where an object of another type is expected. We’ll have more to say about conversions in § 4.11 (p. 159), but for now it is useful to understand what happens when we assign a value of one type to an object of another type.

When we assign one arithmetic type to another:

bool b = 42; // b is true

int i = b; // i has value 1

i = 3.14; // i has value 3

double pi = i; // pi has value 3.0

unsigned char c = -1; // assuming 8-bit chars, c has value 255

signed char c2 = 256; // assuming 8-bit chars, the value of c2 is undefined

what happens depends on the range of the values that the types permit:

• When we assign one of the non

boolarithmetic types to aboolobject, the result isfalseif the value is0andtrueotherwise.

• When we assign a

boolto one of the other arithmetic types, the resulting value is1if theboolistrueand0if theboolisfalse.

• When we assign a floating-point value to an object of integral type, the value is truncated. The value that is stored is the part before the decimal point.

• When we assign an integral value to an object of floating-point type, the fractional part is zero. Precision may be lost if the integer has more bits than the floating-point object can accommodate.

• If we assign an out-of-range value to an object of unsigned type, the result is the remainder of the value modulo the number of values the target type can hold. For example, an 8-bit

unsigned charcan hold values from 0 through 255, inclusive. If we assign a value outside this range, the compiler assigns the remainder of that value modulo 256. Therefore, assigning –1 to an 8-bitunsigned chargives that object the value 255.

• If we assign an out-of-range value to an object of signed type, the result is undefined. The program might appear to work, it might crash, or it might produce garbage values.

Undefined behavior results from errors that the compiler is not required (and sometimes is not able) to detect. Even if the code compiles, a program that executes an undefined expression is in error.

Unfortunately, programs that contain undefined behavior can appear to execute correctly in some circumstances and/or on some compilers. There is no guarantee that the same program, compiled under a different compiler or even a subsequent release of the same compiler, will continue to run correctly. Nor is there any guarantee that what works with one set of inputs will work with another.

Similarly, programs usually should avoid implementation-defined behavior, such as assuming that the size of an

intis a fixed and known value. Such programs are said to be nonportable. When the program is moved to another machine, code that relied on implementation-defined behavior may fail. Tracking down these sorts of problems in previously working programs is, mildly put, unpleasant.

The compiler applies these same type conversions when we use a value of one arithmetic type where a value of another arithmetic type is expected. For example, when we use a nonbool value as a condition (§ 1.4.1, p. 12), the arithmetic value is converted to bool in the same way that it would be converted if we had assigned that arithmetic value to a bool variable:

int i = 42;

if (i) // condition will evaluate as true

i = 0;

If the value is 0, then the condition is false; all other (nonzero) values yield true.

By the same token, when we use a bool in an arithmetic expression, its value always converts to either 0 or 1. As a result, using a bool in an arithmetic expression is almost surely incorrect.

Although we are unlikely to intentionally assign a negative value to an object of unsigned type, we can (all too easily) write code that does so implicitly. For example, if we use both unsigned and int values in an arithmetic expression, the int value ordinarily is converted to unsigned. Converting an int to unsigned executes the same way as if we assigned the int to an unsigned:

unsigned u = 10;

int i = -42;

std::cout << i + i << std::endl; // prints -84

std::cout << u + i << std::endl; // if 32-bit ints, prints 4294967264

In the first expression, we add two (negative) int values and obtain the expected result. In the second expression, the int value -42 is converted to unsigned before the addition is done. Converting a negative number to unsigned behaves exactly as if we had attempted to assign that negative value to an unsigned object. The value “wraps around” as described above.

Regardless of whether one or both operands are unsigned, if we subtract a value from an unsigned, we must be sure that the result cannot be negative:

unsigned u1 = 42, u2 = 10;

std::cout << u1 - u2 << std::endl; // ok: result is 32

std::cout << u2 - u1 << std::endl; // ok: but the result will wrap around

The fact that an unsigned cannot be less than zero also affects how we write loops. For example, in the exercises to § 1.4.1 (p. 13), you were to write a loop that used the decrement operator to print the numbers from 10 down to 0. The loop you wrote probably looked something like

for (int i = 10; i >= 0; --i)

std::cout << i << std::endl;

We might think we could rewrite this loop using an unsigned. After all, we don’t plan to print negative numbers. However, this simple change in type means that our loop will never terminate:

// WRONG: u can never be less than 0; the condition will always succeed

for (unsigned u = 10; u >= 0; --u)

std::cout << u << std::endl;

Consider what happens when u is 0. On that iteration, we’ll print 0 and then execute the expression in the for loop. That expression, --u, subtracts 1 from u. That result, -1, won’t fit in an unsigned value. As with any other out-of-range value, -1 will be transformed to an unsigned value. Assuming 32-bit ints, the result of --u, when u is 0, is 4294967295.

One way to write this loop is to use a while instead of a for. Using a while lets us decrement before (rather than after) printing our value:

unsigned u = 11; // start the loop one past the first element we want to print

while (u > 0) {

--u; // decrement first, so that the last iteration will print 0

std::cout << u << std::endl;

}

This loop starts by decrementing the value of the loop control variable. On the last iteration, u will be 1 on entry to the loop. We’ll decrement that value, meaning that we’ll print 0 on this iteration. When we next test u in the while condition, its value will be 0 and the loop will exit. Because we start by decrementing u, we have to initialize u to a value one greater than the first value we want to print. Hence, we initialize u to 11, so that the first value printed is 10.

Expressions that mix signed and unsigned values can yield surprising results when the signed value is negative. It is essential to remember that signed values are automatically converted to unsigned. For example, in an expression like

a * b, ifais-1andbis1, then if bothaandbareints, the value is, as expected-1. However, ifaisintandbis anunsigned, then the value of this expression depends on how many bits aninthas on the particular machine. On our machine, this expression yields4294967295.

Exercises Section 2.1.2

unsigned u = 10, u2 = 42;

std::cout << u2 - u << std::endl;

std::cout << u - u2 << std::endl;

int i = 10, i2 = 42;

std::cout << i2 - i << std::endl;

std::cout << i - i2 << std::endl;

std::cout << i - u << std::endl;

std::cout << u - i << std::endl;Exercise 2.4: Write a program to check whether your predictions were correct. If not, study this section until you understand what the problem is.

A value, such as 42, is known as a literal because its value self-evident. Every literal has a type. The form and value of a literal determine its type.

We can write an integer literal using decimal, octal, or hexadecimal notation. Integer literals that begin with 0 (zero) are interpreted as octal. Those that begin with either 0x or 0X are interpreted as hexadecimal. For example, we can write the value 20 in any of the following three ways:

20 /* decimal */ 024 /* octal */ 0x14 /* hexadecimal */

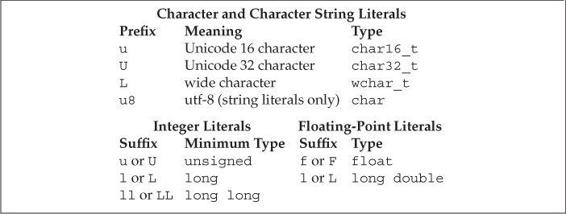

The type of an integer literal depends on its value and notation. By default, decimal literals are signed whereas octal and hexadecimal literals can be either signed or unsigned types. A decimal literal has the smallest type of int, long, or long long (i.e., the first type in this list) in which the literal’s value fits. Octal and hexadecimal literals have the smallest type of int, unsigned int, long, unsigned long, long long, or unsigned long long in which the literal’s value fits. It is an error to use a literal that is too large to fit in the largest related type. There are no literals of type short. We’ll see in Table 2.2 (p. 40) that we can override these defaults by using a suffix.

Table 2.2. Specifying the Type of a Literal

Although integer literals may be stored in signed types, technically speaking, the value of a decimal literal is never a negative number. If we write what appears to be a negative decimal literal, for example, -42, the minus sign is not part of the literal. The minus sign is an operator that negates the value of its (literal) operand.

Floating-point literals include either a decimal point or an exponent specified using scientific notation. Using scientific notation, the exponent is indicated by either E or e:

3.14159 3.14159E0 0. 0e0 .001

By default, floating-point literals have type double. We can override the default using a suffix from Table 2.2 (overleaf).

A character enclosed within single quotes is a literal of type char. Zero or more characters enclosed in double quotation marks is a string literal:

'a' // character literal

"Hello World!" // string literal

The type of a string literal is array of constant chars, a type we’ll discuss in § 3.5.4 (p. 122). The compiler appends a null character (’\0’) to every string literal. Thus, the actual size of a string literal is one more than its apparent size. For example, the literal 'A' represents the single character A, whereas the string literal "A" represents an array of two characters, the letter A and the null character.

Two string literals that appear adjacent to one another and that are separated only by spaces, tabs, or newlines are concatenated into a single literal. We use this form of literal when we need to write a literal that would otherwise be too large to fit comfortably on a single line:

// multiline string literal

std::cout << "a really, really long string literal "

"that spans two lines" << std::endl;

Some characters, such as backspace or control characters, have no visible image. Such characters are nonprintable. Other characters (single and double quotation marks, question mark, and backslash) have special meaning in the language. Our programs cannot use any of these characters directly. Instead, we use an escape sequence to represent such characters. An escape sequence begins with a backslash. The language defines several escape sequences:

newline

\nhorizontal tab\talert (bell)\a

vertical tab\vbackspace\bdouble quote\"

backslash\\question mark\?single quote\'

carriage return\rformfeed\f

We use an escape sequence as if it were a single character:

std::cout << '\n'; // prints a newline

std::cout << "\tHi!\n"; // prints a tab followd by "Hi!" and a newline

We can also write a generalized escape sequence, which is \x followed by one or more hexadecimal digits or a \ followed by one, two, or three octal digits. The value represents the numerical value of the character. Some examples (assuming the Latin-1 character set):

\7 (bell) \12 (newline) \40 (blank)null

\0 () \115 ('M') \x4d ('M')

As with an escape sequence defined by the language, we use these escape sequences as we would any other character:

std::cout << "Hi \x4dO\115!\n"; // prints Hi MOM! followed by a newline

std::cout << '\115' << '\n'; // prints M followed by a newline

Note that if a \ is followed by more than three octal digits, only the first three are associated with the \. For example, "\1234" represents two characters: the character represented by the octal value 123 and the character 4. In contrast, \x uses up all the hex digits following it; "\x1234" represents a single, 16-bit character composed from the bits corresponding to these four hexadecimal digits. Because most machines have 8-bit chars, such values are unlikely to be useful. Ordinarily, hexadecimal characters with more than 8 bits are used with extended characters sets using one of the prefixes from Table 2.2.

We can override the default type of an integer, floating- point, or character literal by supplying a suffix or prefix as listed in Table 2.2.

L'a' // wide character literal, type is wchar_t

u8"hi!" // utf-8 string literal (utf-8 encodes a Unicode character in 8 bits)

42ULL // unsigned integer literal, type is unsigned long long

1E-3F // single-precision floating-point literal, type is float

3.14159L // extended-precision floating-point literal, type is long double

When you write a

longliteral, use the uppercaseL; the lowercase letterlis too easily mistaken for the digit 1.

We can independently specify the signedness and size of an integral literal. If the suffix contains a U, then the literal has an unsigned type, so a decimal, octal, or hexadecimal literal with a U suffix has the smallest type of unsigned int, unsigned long, or unsigned long long in which the literal’s value fits. If the suffix contains an L, then the literal’s type will be at least long; if the suffix contains LL, then the literal’s type will be either long long or unsigned long long. We can combine U with either L or LL. For example, a literal with a suffix of UL will be either unsigned long or unsigned long long, depending on whether its value fits in unsigned long.

The words true and false are literals of type bool:

bool test = false;

The word nullptr is a pointer literal. We’ll have more to say about pointers and nullptr in § 2.3.2 (p. 52).

Exercises Section 2.1.3

Exercise 2.5: Determine the type of each of the following literals. Explain the differences among the literals in each of the four examples:

(a)

'a',L'a',"a",L"a"(b)

10,10u,10L,10uL,012,0xC(c)

3.14,3.14f,3.14L(d)

10,10u,10.,10e-2Exercise 2.6: What, if any, are the differences between the following definitions:

int month = 9, day = 7;

int month = 09, day = 07;Exercise 2.7: What values do these literals represent? What type does each have?

(a)

"Who goes with F\145rgus?\012"(b)

3.14e1L(c)

1024f(d)

3.14LExercise 2.8: Using escape sequences, write a program to print

2Mfollowed by a newline. Modify the program to print2, then a tab, then anM, followed by a newline.