18.3. Multiple and Virtual Inheritance

Multiple inheritance is the ability to derive a class from more than one direct base class (§ 15.2.2, p. 600). A multiply derived class inherits the properties of all its parents. Although simple in concept, the details of intertwining multiple base classes can present tricky design-level and implementation-level problems.

To explore multiple inheritance, we’ll use a pedagogical example of a zoo animal hierarchy. Our zoo animals exist at different levels of abstraction. There are the individual animals, distinguished by their names, such as Ling-ling, Mowgli, and Balou. Each animal belongs to a species; Ling-Ling, for example, is a giant panda. Species, in turn, are members of families. A giant panda is a member of the bear family. Each family, in turn, is a member of the animal kingdom—in this case, the more limited kingdom of a particular zoo.

We’ll define an abstract ZooAnimal class to hold information that is common to all the zoo animals and provides the most general interface. The Bear class will contain information that is unique to the Bear family, and so on.

In addition to the ZooAnimal classes, our application will contain auxiliary classes that encapsulate various abstractions such as endangered animals. In our implementation of a Panda class, for example, a Panda is multiply derived from Bear and Endangered.

18.3.1. Multiple Inheritance

The derivation list in a derived class can contain more than one base class:

class Bear : public ZooAnimal {

class Panda : public Bear, public Endangered { /* ... */ };Each base class has an optional access specifier (§ 15.5, p. 612). As usual, if the access specifier is omitted, the specifier defaults to private if the class keyword is used and to public if struct is used (§ 15.5, p. 616).

As with single inheritance, the derivation list may include only classes that have been defined and that were not defined as final (§ 15.2.2, p. 600). There is no language-imposed limit on the number of base classes from which a class can be derived. A base class may appear only once in a given derivation list.

Multiply Derived Classes Inherit State from Each Base Class

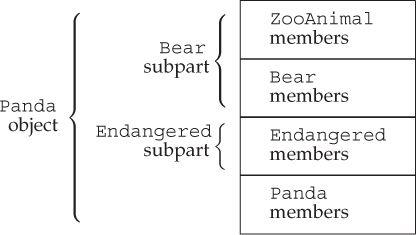

Under multiple inheritance, an object of a derived class contains a subobject for each of its base classes (§ 15.2.2, p. 597). For example, as illustrated in Figure 18.2, a Panda object has a Bear part (which itself contains a ZooAnimal part), an Endangered class part, and the nonstatic data members, if any, declared within the Panda class.

Figure 18.2. Conceptual Structure of a Panda Object

Derived Constructors Initialize All Base Classes

Constructing an object of derived type constructs and initializes all its base subobjects. As is the case for inheriting from a single base class (§ 15.2.2, p. 598), a derived type’s constructor initializer may initialize only its direct base classes:

// explicitly initialize both base classes

Panda::Panda(std::string name, bool onExhibit)

: Bear(name, onExhibit, "Panda"),

Endangered(Endangered::critical) { }

// implicitly uses the Bear default constructor to initialize the Bear subobject

Panda::Panda()

: Endangered(Endangered::critical) { }The constructor initializer list may pass arguments to each of the direct base classes. The order in which base classes are constructed depends on the order in which they appear in the class derivation list. The order in which they appear in the constructor initializer list is irrelevant. A Panda object is initialized as follows:

ZooAnimal, the ultimate base class up the hierarchy fromPanda’s first direct base class,Bear, is initialized first.Bear, the first direct base class, is initialized next.Endangered, the second direct base, is initialized next.Panda, the most derived part, is initialized last.

Inherited Constructors and Multiple Inheritance

C++11Under the new standard, a derived class can inherit its constructors from one or more of its base classes (§ 15.7.4, p. 628). It is an error to inherit the same constructor (i.e., one with the same parameter list) from more than one base class:

struct Base1 {

Base1() = default;

Base1(const std::string&);

Base1(std::shared_ptr<int>);

};

struct Base2 {

Base2() = default;

Base2(const std::string&);

Base2(int);

};

// error: D1 attempts to inherit D1::D1 (const string&) from both base classes

struct D1: public Base1, public Base2 {

using Base1::Base1; // inherit constructors from Base1

using Base2::Base2; // inherit constructors from Base2

};A class that inherits the same constructor from more than one base class must define its own version of that constructor:

struct D2: public Base1, public Base2 {

using Base1::Base1; // inherit constructors from Base1

using Base2::Base2; // inherit constructors from Base2

// D2 must define its own constructor that takes a string

D2(const string &s): Base1(s), Base2(s) { }

D2() = default; // needed once D2 defines its own constructor

};Destructors and Multiple Inheritance

As usual, the destructor in a derived class is responsible for cleaning up resources allocated by that class only—the members and all the base class(es) of the derived class are automatically destroyed. The synthesized destructor has an empty function body.

Destructors are always invoked in the reverse order from which the constructors are run. In our example, the order in which the destructors are called is ~Panda, ~Endangered, ~Bear, ~ZooAnimal.

Copy and Move Operations for Multiply Derived Classes

As is the case for single inheritance, classes with multiple bases that define their own copy/move constructors and assignment operators must copy, move, or assign the whole object (§ 15.7.2, p. 623). The base parts of a multiply derived class are automatically copied, moved, or assigned only if the derived class uses the synthesized versions of these members. In the synthesized copy-control members, each base class is implicitly constructed, assigned, or destroyed, using the corresponding member from that base class.

For example, assuming that Panda uses the synthesized members, then the initialization of ling_ling:

Panda ying_yang("ying_yang");

Panda ling_ling = ying_yang; // uses the copy constructorwill invoke the Bear copy constructor, which in turn runs the ZooAnimal copy constructor before executing the Bear copy constructor. Once the Bear portion of ling_ling is constructed, the Endangered copy constructor is run to create that part of the object. Finally, the Panda copy constructor is run. Similarly, for the synthesized move constructor.

The synthesized copy-assignment operator behaves similarly to the copy constructor. It assigns the Bear (and through Bear, the ZooAnimal) parts of the object first. Next, it assigns the Endangered part, and finally the Panda part. Move assignment behaves similarly.

18.3.2. Conversions and Multiple Base Classes

Under single inheritance, a pointer or a reference to a derived class can be converted automatically to a pointer or a reference to an accessible base class (§ 15.2.2, p. 597, and § 15.5, p. 613). The same holds true with multiple inheritance. A pointer or reference to any of an object’s (accessible) base classes can be used to point or refer to a derived object. For example, a pointer or reference to ZooAnimal, Bear, or Endangered can be bound to a Panda object:

// operations that take references to base classes of type Panda

void print(const Bear&);

void highlight(const Endangered&);

ostream& operator<<(ostream&, const ZooAnimal&);

Panda ying_yang("ying_yang");

print(ying_yang); // passes Panda to a reference to Bear

highlight(ying_yang); // passes Panda to a reference to Endangered

cout << ying_yang << endl; // passes Panda to a reference to ZooAnimalINFO

Exercises Section 18.3.1

Exercise 18.21: Explain the following declarations. Identify any that are in error and explain why they are incorrect:

(a)class CADVehicle : public CAD, Vehicle { ... };

(b)class DblList: public List, public List { ... };

(c)class iostream: public istream, public ostream { ... };

Exercise 18.22: Given the following class hierarchy, in which each class defines a default constructor:

class A { ... };

class B : public A { ... };

class C : public B { ... };

class X { ... };

class Y { ... };

class Z : public X, public Y { ... };

class MI : public C, public Z { ... };what is the order of constructor execution for the following definition?

MI mi;The compiler makes no attempt to distinguish between base classes in terms of a derived-class conversion. Converting to each base class is equally good. For example, if there was an overloaded version of print:

void print(const Bear&);

void print(const Endangered&);an unqualified call to print with a Panda object would be a compile-time error:

Panda ying_yang("ying_yang");

print(ying_yang); // error: ambiguousLookup Based on Type of Pointer or Reference

As with single inheritance, the static type of the object, pointer, or reference determines which members we can use (§ 15.6, p. 617). If we use a ZooAnimal pointer, only the operations defined in that class are usable. The Bear-specific, Panda-specific, and Endangered portions of the Panda interface are invisible. Similarly, a Bear pointer or reference knows only about the Bear and ZooAnimal members; an Endangered pointer or reference is limited to the Endangered members.

As an example, consider the following calls, which assume that our classes define the virtual functions listed in Table 18.1:

Bear *pb = new Panda("ying_yang");

pb->print(); // ok: Panda::print()

pb->cuddle(); // error: not part of the Bear interface

pb->highlight(); // error: not part of the Bear interface

delete pb; // ok: Panda::~Panda()When a Panda is used via an Endangered pointer or reference, the Panda-specific and Bear portions of the Panda interface are invisible:

Endangered *pe = new Panda("ying_yang");

pe->print(); // ok: Panda::print()

pe->toes(); // error: not part of the Endangered interface

pe->cuddle(); // error: not part of the Endangered interface

pe->highlight(); // ok: Panda::highlight()

delete pe; // ok: Panda::~Panda()Table 18.1. Virtual Functions in the ZooAnimal/Endangered Classes

| Function | Class Defining Own Version |

|---|---|

print | ZooAnimal::ZooAnimalBear::BearEndangered::EndangeredPanda::Panda |

highlight | Endangered::EndangeredPanda::Panda |

toes | Bear::BearPanda::Panda |

cuddle | Panda::Panda |

| destructor | ZooAnimal::ZooAnimalEndangered::Endangered |

18.3.3. Class Scope under Multiple Inheritance

Under single inheritance, the scope of a derived class is nested within the scope of its direct and indirect base classes (§ 15.6, p. 617). Lookup happens by searching up the inheritance hierarchy until the given name is found. Names defined in a derived class hide uses of that name inside a base.

Under multiple inheritance, this same lookup happens simultaneously among all the direct base classes. If a name is found through more than one base class, then use of that name is ambiguous.

INFO

Exercises Section 18.3.2

Exercise 18.23: Using the hierarchy in exercise 18.22 along with class D defined below, and assuming each class defines a default constructor, which, if any, of the following conversions are not permitted?

class D : public X, public C { ... };

D *pd = new D;(a)X *px = pd;

(b)A *pa = pd;

(c)B *pb = pd;

(d)C *pc = pd;

Exercise 18.24: On page 807 we presented a series of calls made through a Bear pointer that pointed to a Panda object. Explain each call assuming we used a ZooAnimal pointer pointing to a Panda object instead.

Exercise 18.25: Assume we have two base classes, Base1 and Base2, each of which defines a virtual member named print and a virtual destructor. From these base classes we derive the following classes, each of which redefines the print function:

class D1 : public Base1 { /* ... */ };

class D2 : public Base2 { /* ... */ };

class MI : public D1, public D2 { /* ... */ };Using the following pointers, determine which function is used in each call:

Base1 *pb1 = new MI;

Base2 *pb2 = new MI;

D1 *pd1 = new MI;

D2 *pd2 = new MI;(a)pb1->print();

(b)pd1->print();

(c)pd2->print();

(d)delete pb2;

(e)delete pd1;

(f)delete pd2;

In our example, if we use a name through a Panda object, pointer, or reference, both the Endangered and the Bear/ZooAnimal subtrees are examined in parallel. If the name is found in more than one subtree, then the use of the name is ambiguous. It is perfectly legal for a class to inherit multiple members with the same name. However, if we want to use that name, we must specify which version we want to use.

WARNING

When a class has multiple base classes, it is possible for that derived class to inherit a member with the same name from two or more of its base classes. Unqualified uses of that name are ambiguous.

For example, if both ZooAnimal and Endangered define a member named max_weight, and Panda does not define that member, this call is an error:

double d = ying_yang.max_weight();The derivation of Panda, which results in Panda having two members named max_weight, is perfectly legal. The derivation generates a potential ambiguity. That ambiguity is avoided if no Panda object ever calls max_weight. The error would also be avoided if each call to max_weight specifically indicated which version to run—ZooAnimal::max_weight or Endangered::max_weight. An error results only if there is an ambiguous attempt to use the member.

The ambiguity of the two inherited max_weight members is reasonably obvious. It might be more surprising to learn that an error would be generated even if the two inherited functions had different parameter lists. Similarly, it would be an error even if the max_weight function were private in one class and public or protected in the other. Finally, if max_weight were defined in Bear and not in ZooAnimal, the call would still be in error.

As always, name lookup happens before type checking (§ 6.4.1, p. 234). When the compiler finds max_weight in two different scopes, it generates an error noting that the call is ambiguous.

The best way to avoid potential ambiguities is to define a version of the function in the derived class that resolves the ambiguity. For example, we should give our Panda class a max_weight function that resolves the ambiguity:

double Panda::max_weight() const

{

return std::max(ZooAnimal::max_weight(),

Endangered::max_weight());

}INFO

Exercises Section 18.3.3

Exercise 18.26: Given the hierarchy in the box on page 810, why is the following call to print an error? Revise MI to allow this call to print to compile and execute correctly.

MI mi;

mi.print(42);Exercise 18.27: Given the class hierarchy in the box on page 810 and assuming we add a function named foo to MI as follows:

int ival;

double dval;

void MI::foo(double cval)

{

int dval;

// exercise questions occur here

}(a) List all the names visible from within MI::foo.

(b) Are any names visible from more than one base class?

(c) Assign to the local instance of dval the sum of the dval member of Base1 and the dval member of Derived.

(d) Assign the value of the last element in MI::dvec to Base2::fval.

(e) Assign cval from Base1 to the first character in sval from Derived.

INFO

Code for Exercises to Section 18.3.3

struct Base1 {

void print(int) const; // public by default

protected:

int ival;

double dval;

char cval;

private:

int *id;

};

struct Base2 {

void print(double) const; // public by default

protected:

double fval;

private:

double dval;

};

struct Derived : public Base1 {

void print(std::string) const; // public by default

protected:

std::string sval;

double dval;

};

struct MI : public Derived, public Base2 {

void print(std::vector<double>); // public by default

protected:

int *ival;

std::vector<double> dvec;

};18.3.4. Virtual Inheritance

Although the derivation list of a class may not include the same base class more than once, a class can inherit from the same base class more than once. It might inherit the same base indirectly from two of its own direct base classes, or it might inherit a particular class directly and indirectly through another of its base classes.

As an example, the IO library istream and ostream classes each inherit from a common abstract base class named basic_ios. That class holds the stream’s buffer and manages the stream’s condition state. The class iostream, which can both read and write to a stream, inherits directly from both istream and ostream. Because both types inherit from basic_ios, iostream inherits that base class twice, once through istream and once through ostream.

By default, a derived object contains a separate subpart corresponding to each class in its derivation chain. If the same base class appears more than once in the derivation, then the derived object will have more than one subobject of that type.

This default doesn’t work for a class such as iostream. An iostream object wants to use the same buffer for both reading and writing, and it wants its condition state to reflect both input and output operations. If an iostream object has two copies of its basic_ios class, this sharing isn’t possible.

In C++ we solve this kind of problem by using virtual inheritance. Virtual inheritance lets a class specify that it is willing to share its base class. The shared base-class subobject is called a virtual base class. Regardless of how often the same virtual base appears in an inheritance hierarchy, the derived object contains only one, shared subobject for that virtual base class.

A Different Panda Class

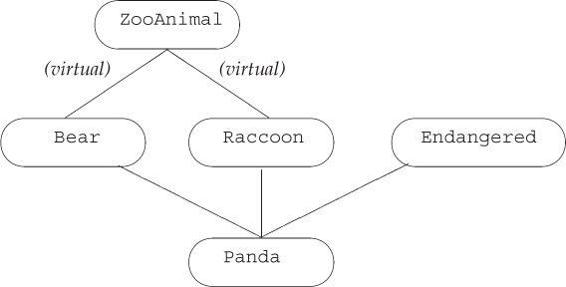

In the past, there was some debate as to whether panda belongs to the raccoon or the bear family. To reflect this debate, we can change Panda to inherit from both Bear and Raccoon. To avoid giving Panda two ZooAnimal base parts, we’ll define Bear and Raccoon to inherit virtually from ZooAnimal. Figure 18.3 illustrates our new hierarchy.

Figure 18.3. Virtual Inheritance Panda Hierarchy

Looking at our new hierarchy, we’ll notice a nonintuitive aspect of virtual inheritance. The virtual derivation has to be made before the need for it appears. For example, in our classes, the need for virtual inheritance arises only when we define Panda. However, if Bear and Raccoon had not specified virtual on their derivation from ZooAnimal, the designer of the Panda class would be out of luck.

In practice, the requirement that an intermediate base class specify its inheritance as virtual rarely causes any problems. Ordinarily, a class hierarchy that uses virtual inheritance is designed at one time either by one individual or by a single project design group. It is exceedingly rare for a class to be developed independently that needs a virtual base in one of its base classes and in which the developer of the new base class cannot change the existing hierarchy.

INFO

Virtual derivation affects the classes that subsequently derive from a class with a virtual base; it doesn’t affect the derived class itself.

Using a Virtual Base Class

We specify that a base class is virtual by including the keyword virtual in the derivation list:

// the order of the keywords public and virtual is not significant

class Raccoon : public virtual ZooAnimal { /* ... */ };

class Bear : virtual public ZooAnimal { /* ... */ };Here we’ve made ZooAnimal a virtual base class of both Bear and Raccoon.

The virtual specifier states a willingness to share a single instance of the named base class within a subsequently derived class. There are no special constraints on a class used as a virtual base class.

We do nothing special to inherit from a class that has a virtual base:

class Panda : public Bear,

public Raccoon, public Endangered {

};Here Panda inherits ZooAnimal through both its Raccoon and Bear base classes. However, because those classes inherited virtually from ZooAnimal, Panda has only one ZooAnimal base subpart.

Normal Conversions to Base Are Supported

An object of a derived class can be manipulated (as usual) through a pointer or a reference to an accessible base-class type regardless of whether the base class is virtual. For example, all of the following Panda base-class conversions are legal:

void dance(const Bear&);

void rummage(const Raccoon&);

ostream& operator<<(ostream&, const ZooAnimal&);

Panda ying_yang;

dance(ying_yang); // ok: passes Panda object as a Bear

rummage(ying_yang); // ok: passes Panda object as a Raccoon

cout << ying_yang; // ok: passes Panda object as a ZooAnimalVisibility of Virtual Base-Class Members

Because there is only one shared subobject corresponding to each shared virtual base, members in that base can be accessed directly and unambiguously. Moreover, if a member from the virtual base is overridden along only one derivation path, then that overridden member can still be accessed directly. If the member is overridden by more than one base, then the derived class generally must define its own version as well.

For example, assume class B defines a member named x; class D1 inherits virtually from B as does class D2; and class D inherits from D1 and D2. From the scope of D, x is visible through both of its base classes. If we use x through a D object, there are three possibilities:

- If

xis not defined in eitherD1orD2it will be resolved as a member inB; there is no ambiguity. ADobject contains only one instance ofx. - If

xis a member ofBand also a member in one, but not both, ofD1andD2, there is again no ambiguity—the version in the derived class is given precedence over the shared virtual base class,B. - If

xis defined in bothD1andD2, then direct access to that member is ambiguous.

As in a nonvirtual multiple inheritance hierarchy, ambiguities of this sort are best resolved by the derived class providing its own instance of that member.

INFO

Exercises Section 18.3.4

Exercise 18.28: Given the following class hierarchy, which inherited members can be accessed without qualification from within the VMI class? Which require qualification? Explain your reasoning.

struct Base {

void bar(int); // public by default

protected:

int ival;

};

struct Derived1 : virtual public Base {

void bar(char); // public by default

void foo(char);

protected:

char cval;

};

struct Derived2 : virtual public Base {

void foo(int); // public by default

protected:

int ival;

char cval;

};

class VMI : public Derived1, public Derived2 { };18.3.5. Constructors and Virtual Inheritance

In a virtual derivation, the virtual base is initialized by the most derived constructor. In our example, when we create a Panda object, the Panda constructor alone controls how the ZooAnimal base class is initialized.

To understand this rule, consider what would happen if normal initialization rules applied. In that case, a virtual base class might be initialized more than once. It would be initialized along each inheritance path that contains that virtual base. In our ZooAnimal example, if normal initialization rules applied, both Bear and Raccoon would initialize the ZooAnimal part of a Panda object.

Of course, each class in the hierarchy might at some point be the “most derived” object. As long as we can create independent objects of a type derived from a virtual base, the constructors in that class must initialize its virtual base. For example, in our hierarchy, when a Bear (or a Raccoon) object is created, there is no further derived type involved. In this case, the Bear (or Raccoon) constructors directly initialize their ZooAnimal base as usual:

Bear::Bear(std::string name, bool onExhibit):

ZooAnimal(name, onExhibit, "Bear") { }

Raccoon::Raccoon(std::string name, bool onExhibit)

: ZooAnimal(name, onExhibit, "Raccoon") { }When a Panda is created, it is the most derived type and controls initialization of the shared ZooAnimal base. Even though ZooAnimal is not a direct base of Panda, the Panda constructor initializes ZooAnimal:

Panda::Panda(std::string name, bool onExhibit)

: ZooAnimal(name, onExhibit, "Panda"),

Bear(name, onExhibit),

Raccoon(name, onExhibit),

Endangered(Endangered::critical),

sleeping_flag(false) { }How a Virtually Inherited Object Is Constructed

The construction order for an object with a virtual base is slightly modified from the normal order: The virtual base subparts of the object are initialized first, using initializers provided in the constructor for the most derived class. Once the virtual base subparts of the object are constructed, the direct base subparts are constructed in the order in which they appear in the derivation list.

For example, when a Panda object is created:

- The (virtual base class)

ZooAnimalpart is constructed first, using the initializers specified in thePandaconstructor initializer list. - The

Bearpart is constructed next. - The

Raccoonpart is constructed next. - The third direct base,

Endangered, is constructed next. - Finally, the

Pandapart is constructed.

If the Panda constructor does not explicitly initialize the ZooAnimal base class, then the ZooAnimal default constructor is used. If ZooAnimal doesn’t have a default constructor, then the code is in error.

INFO

Virtual base classes are always constructed prior to nonvirtual base classes regardless of where they appear in the inheritance hierarchy.

Constructor and Destructor Order

A class can have more than one virtual base class. In that case, the virtual subobjects are constructed in left-to-right order as they appear in the derivation list. For example, in the following whimsical TeddyBear derivation, there are two virtual base classes: ToyAnimal, a direct virtual base, and ZooAnimal, which is a virtual base class of Bear:

class Character { /* ... */ };

class BookCharacter : public Character { /* ... */ };

class ToyAnimal { /* ... */ };

class TeddyBear : public BookCharacter,

public Bear, public virtual ToyAnimal

{ /* ... */ };The direct base classes are examined in declaration order to determine whether there are any virtual base classes. If so, the virtual bases are constructed first, followed by the nonvirtual base-class constructors in declaration order. Thus, to create a TeddyBear, the constructors are invoked in the following order:

ZooAnimal(); // Bear's virtual base class

ToyAnimal(); // direct virtual base class

Character(); // indirect base class of first nonvirtual base class

BookCharacter(); // first direct nonvirtual base class

Bear(); // second direct nonvirtual base class

TeddyBear(); // most derived classThe same order is used in the synthesized copy and move constructors, and members are assigned in this order in the synthesized assignment operators. As usual, an object is destroyed in reverse order from which it was constructed. The TeddyBear part will be destroyed first and the ZooAnimal part last.

INFO

Exercises Section 18.3.5

Exercise 18.29: Given the following class hierarchy:

class Class { ... };

class Base : public Class { ... };

class D1 : virtual public Base { ... };

class D2 : virtual public Base { ... };

class MI : public D1, public D2 { ... };

class Final : public MI, public Class { ... };(a) In what order are constructors and destructors run on a Final object?

(b) A Final object has how many Base parts? How many Class parts?

(c) Which of the following assignments is a compile-time error?

Base *pb; Class *pc; MI *pmi; D2 *pd2;(a)pb = new Class;

(b)pc = new Final;

(c)pmi = pb;

(d)pd2 = pmi;

Exercise 18.30: Define a default constructor, a copy constructor, and a constructor that has an int parameter in Base. Define the same three constructors in each derived class. Each constructor should use its argument to initialize its Base part.